Is Dried Fruit Good For You? A Nutritionist’s Perspective

I’d say a lot of Nutritionists, myself included, have neglected to put much emphasis on dried fruit as a staple part of a healthy diet – but my tune is now changing. After taking a look at the existing research on dried fruit, I can confidently say I’m impressed with what I’ve learned.

I have distinct memories of being at preschool, sitting on a bench seat during morning tea. Day after day, under the Queensland summer sun, you’d find me with a little box of sultanas squarely in the palm of my hand.

Over the years, I’d come to know currants, raisins and dried apricots, either as afternoon snacks or as the main event in mum’s Christmas pudding. And recently, flicking through my great-grandmother’s leather-bound cookbook, I found a simple recipe for a ‘homemade laxative’, of course with prunes as the star ingredient!

It turns out there’s a mountain of papers suggesting the various positive effects of many dried fruits on digestive function, appetite regulation, insulin activity, tumour suppression and osteoporosis prevention and more!

What is dried fruit?

Traditionally, the term ‘dried fruit’ refers to any whole or cut fruit that has been dried by heat, air or the sun. Popular among our hunter-gatherer ancestors and more recently as a means to ensure food lasted throughout the winter, dried fruits pop up everywhere throughout history and across cultures.

Common examples are dates, prunes, figs, apricots, sultanas and raisins. Almost all fruit can be dried, freeze-dried or dehydrated. Some other popular additions to the dried fruit category include bananas, mangoes, apples, pears and berries.

Some are naturally dried and packaged without preservatives; others have preservatives added to maintain their appearance and shelf life, while others might have added sugar or juice as well.

Dried fruit can be a great healthy alternative to other packaged snacks, storing well and available year-round.

Dried Fruit Nutrition information & Health Benefits – At a Glance

- Low G.I.

- Helps digestive function

- Supports microbiome

- Balances blood glucose

- Promotes bone growth

- Supports cardiovascular function

- Anti-cancer properties

- Supports men’s reproductive function

- Regulates hormones

- Healthy pregnancy outcomes

- Osteoporosis management

Contrary to popular belief, the overall sugar content in dried fruits such as plums, apricots, raisins and sultanas is relatively low in comparison to the fibre and total polyphenol content.

This means they are naturally-low GI foods, which do not elicit a spike in blood glucose levels upon consumption. The fibre content also means these foods have a natural laxative effect and can help with healthy bowel function.

Interestingly, the process of drying the fruit appears to concentrate the available micronutrient levels within the fruit. Research shows that compared to their fresh counterparts, up to 5 times increased levels of folate exist in Australian dried sultanas, apricots, currants and prunes. Calcium, magnesium, boron, iron, copper, zinc and selenium are also plentiful in these fruits.

The concentration of polyphenols as well as vitamins and minerals has other meaningful health benefits. Some reports indicate that increasing dried fruit consumption to between three and five servings (about 30g per serve) each week could prevent the development of various types of cancers, including pancreatic, bladder and stomach cancer.

Goji Berries

A berry of Chinese origin and botanically from the Lycium family, Goji berries are nutritionally unrivalled with several traditional and modern uses. They contain modest amounts of copper, manganese, selenium and B vitamins and contain around 13% protein, which is unusual for a berry. This makes it a great healthy dried fruit choice.

Famously touted for possessing anti-aging and immune enhancing properties, the Goji berry has powerful antioxidants, which protect against cellular damage. Carotenoids are a group of phytochemicals found abundantly in Goji berries and are responsible for their brilliant burnt orange and red colours.

Zeaxanthin is the specific carotenoid in Goji berries and a 2019 research paper found that this polyphenol protects the retina and helps maintain blood glucose levels in animal studies. These amazing berries also promote the innate immune system’s ability to inhibit cancer cell growth.

Raisins & Sultanas

A 12-week, randomized and controlled trial compared the consumption of processed snacks with moderate daily raisin consumption. The results demonstrated a significant beneficial effect on blood glucose, blood pressure and overall cardiovascular function at the conclusion of the study.

Sultanas may also help with appetite regulation by influencing the hunger signalling pathways in the gut and increasing satiety (feeling of fullness). This means that raisins and sultanas are considered a functional food, with definite health benefits for people with or developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity.

Figs

The ancient Greeks and Romans revered figs as a symbol of growth, prosperity and wealth. They have natural anti-bacterial and anti-parasitic properties and studies show that sun-dried, naturally-preserved figs possess a higher amount of active plant compounds. These help to prevent cancer, support digestion and reduce oxidative stress in the body.

Figs are also traditionally known for supporting male reproductive function, specifically sperm motility and quality. The antioxidants found in figs protect the lipoproteins in blood serum from free radical cell damage.

Dried Mango

Mangiferin found in dried mango possesses antioxidant and hypoglycaemic properties. Dried mango can be helpful in regulating blood glucose and maintaining a healthy heart.

Dates

Historically, dates have been used in traditional medicine for tissue healing, respiratory disease, digestive disorders and fever.

The natural fibre helps support beneficial microbial growth in the bowel, which enhances digestion and immunity. Dates have the highest polyphenol content of all dried fruit and along with figs have the most complex nutrient levels.

Despite their sweet taste, the sugar content in dates is actually low to moderate. This means you won’t get a glucose spike from eating them.

The most compelling research in support of date consumption is in pregnancy and childbirth. Several studies show that eating dates in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy helps to facilitate cervical dilation, and prepares the body for labour by stimulating oxytocin receptors in the uterus.

The authors from a 2017 meta-analysis found that around 50g of daily date consumption reduced the active phase of labour in healthy pregnant women and decreased the need for further medical interventions, including labour induction. This is great news for women seeking to naturally and safely support their body during the final weeks of their pregnancy.

Prunes

Prunes are dried plums and are perhaps most notorious/cherished for their role in reducing constipation. They have been shown to be more effective than an insoluble fibre called psyllium for the treatment of mild to moderate constipation.

Prunes are a good source of antioxidants and protect against LDL cholesterol oxidation, which prevents the development of heart disease and cancer. Another cool and unexpected fact about prunes is that they help prevent osteoporosis. They are high in the mineral boron, which is essential for bone growth and maintenance, particularly in trabecular bone tissue (the hip and joints) as well as the lumbar spine.

Prunes have synergistic polyphenols that modulate bone metabolism. Specifically, they have unique active compounds that slow osteoclastic (bone breakdown) activity while promoting osteoblastic (bone growth) activity. This could be mainly relevant to postmenopausal women.

Even better, Arjmandi et al. & Rendina et al. demonstrated that the bone-protective effects of prunes was prolonged after the regular consumption of the fruit had ceased.

Dried Fruit and Preservatives: what you should know

Drying fruit and maintaining the nutritional value, taste and appearance is no mean feat in the world of food technology. If dried improperly, there is the risk of contamination with mould or bacteria, which spoils food and has potentially hazardous health effects.

One of the toxins produced by these moulds is known as Aflatoxin B1. Classed by the World Health Organisation as a ‘group A’ carcinogen, it is known to be a cause of liver cancer. Long-term exposure to Aflatoxin B1 can also cause immunosuppression.

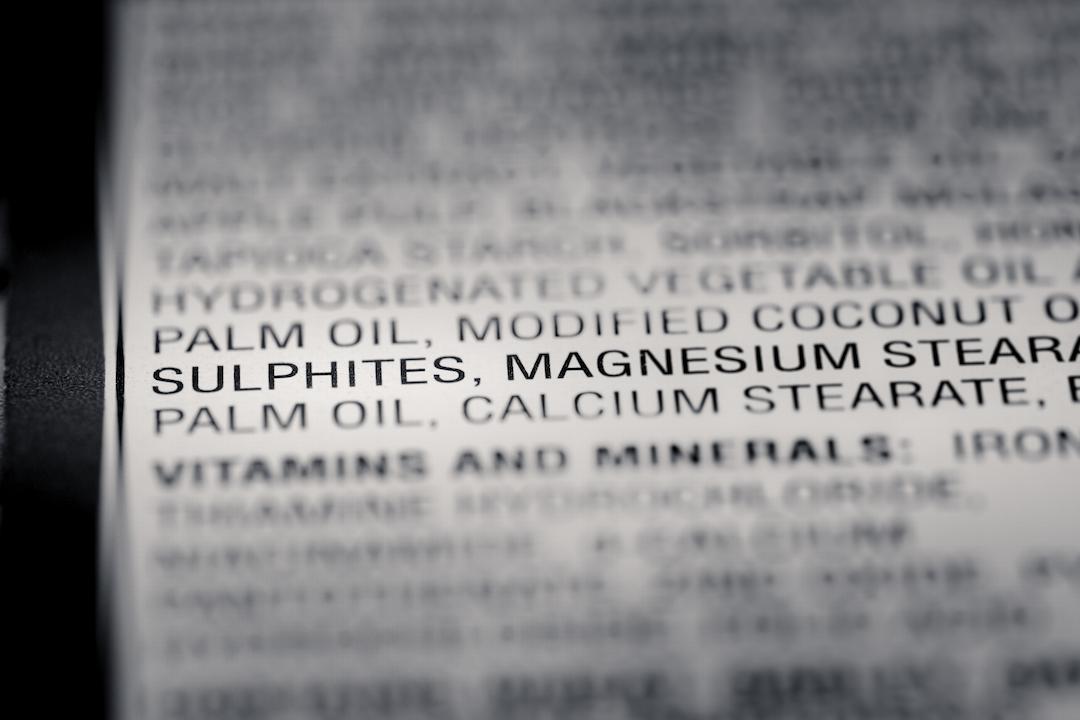

To avoid this issue, chemical preservatives are a necessary part of the fruit drying process in some fruits that have a higher risk of attracting moulds and fungi. Common preservatives used in dried fruit are sulphites or preservatives labelled as the ‘200’s range’.

These days, thankfully, there are regulations around how much of any synthetic ingredient can be safely added to foods. Food Standards Australia & New Zealand (FSANZ) outlines the required safety assessments, which ensure that an additive or preservative is used within a reasonable technological rationale. This means that if a preservative is there, basically it’s because it needs to be. Further, on these occasions there are limits which have been established. These ensure that everyone, including children, can safely consume those dried fruits.

My preference as a mum, Nutritionist and conscious consumer will always be to choose preservative-free. If you can avoid or reduce the chemical load your body experiences on a daily basis, from food and your environment, your overall health will be better.

In clinical practice, preservative sensitivity commonly presents as headaches, nausea, skin flushing, dehydration and digestive upset. Some people have no idea unless they have prolonged exposure to preservatives. Children are especially sensitive to preservatives and the excessive consumption of sulphited-foods should be avoided where possible. The liver has to work hard to process preservatives, which can also disrupt hormone function, interfere with neurotransmitter activity and are linked to immune issues, asthma and cancer.

On balance, it’s just a matter of discerning what works for you. It’s important to choose wisely and moderately, check food labels and be aware of symptoms of potential preservative sensitivity.

Recipe

Mediterranean Lamb Tagine with almonds and prunes

Ingredients

2 tsp. olive oil

1kg cubed lamb

1 large diced onion

1 tin chopped tomato

1 bunch chopped coriander

1 tsp. brown sugar (optional)

1 tsp. ground ginger

½ tsp. pepper

½ tsp. paprika

½ tsp. turmeric

½ tsp. ground coriander seeds

½ tsp. cinnamon

1 cup water

400g prunes

Sea salt to taste

3-4 cups cooked rice or quinoa to serve

2 tbsp. toasted almonds

1 tbsp. toasted sesame seeds

Method

- Heat olive oil In a large heavy pot over medium heat

- Brown lamb on all sides in batches (4-6mins each batch) and set aside

- In same pot, heat oil and sauté onion until soft and just charred

- Add spices and sugar, stir for 1 minute until fragrant

- Return lamb to pot, add tinned tomato, cup of water and coriander

- Cover and bring lamb to a simmer over low heat, stirring occasionally

- Continue to cook for 2 hours adding more water if needed

- In final 10 minutes add prunes and simmer, season if needed.

- Serve with rice or quinoa and sprinkle with toasted almonds and sesame seeds

Shop Now

Australian Dried Apple

Australian Dried Mango

Article References

Ma, Z. F., Zhang, H., Teh, S. S., Wang, C. W., Zhang, Y., Hayford, F., Wang, L., Ma, T., Dong, Z., Zhang, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2019). Goji Berries as a Potential Natural Antioxidant Medicine: An Insight into Their Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2019, 2437397.https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2437397

Zhu, R., Fan, Z., Dong, Y., Liu, M., Wang, L., & Pan, H. (2018). Postprandial Glycaemic Responses of Dried Fruit-Containing Meals in Healthy Adults: Results from a Randomised Trial. Nutrients, 10(6), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060694

Sadler, M. J., Gibson, S., Whelan, K., Ha, M. A., Lovegrove, J., & Higgs, J. (2019). Dried fruit and public health - what does the evidence tell us?. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 70(6), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2019.1568398

O'Meara, Cyndi. (2007). Changing Habits Changing Lives. Penguin Books.

Yurt, B., & Celik, I. (2011). Hepatoprotective effect and antioxidant role of sun, sulphited-dried apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) and its kernel against ethanol-induced oxidative stress in rats. Food and chemical toxicology: an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 49(2), 508–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.035

Arvaniti, O. S., Samaras, Y., Gatidou, G., Thomaidis, N. S., & Stasinakis, A. S. (2019). Review on fresh and dried figs: Chemical analysis and occurrence of phytochemical compounds, antioxidant capacity and health effects. Food research international (Ottawa, Ont.), 119, 244–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.01.055

Choice. (2021). Food and Drink. Food Warnings & Safety. Food Additives You Should Avoid. https://www.choice.com.au/food-and-drink/food-warnings-and-safety/food-additives/articles/food-additives-you-should-avoid

Tournas, V. H., Niazi, N. S., & Kohn, J. S. (2015). Fungal Presence in Selected Tree Nuts and Dried Fruits. Microbiology insights, 8, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4137/MBI.S24308

Food Matters. (2021). The Dangers of Dried Fruit. https://www.foodmatters.com/article/the-dangers-of-dried-fruit

Trucksess, M. W., & Scott, P. M. (2008). Mycotoxins in botanicals and dried fruits: a review. Food additives & contaminants. Part A, Chemistry, analysis, control, exposure & risk assessment, 25(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652030701567459

Magnussen, A., & Parsi, M. A. (2013). Aflatoxins, hepatocellular carcinoma and public health. World journal of gastroenterology, 19(10), 1508–1512. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1508

Eid, N., Osmanova, H., Natchez, C., Walton, G., Costabile, A., Gibson, G., Rowland, I., & Spencer, J. P. (2015). Impact of palm date consumption on microbiota growth and large intestinal health: a randomised, controlled, cross-over, human intervention study. The British journal of nutrition, 114(8), 1226–1236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515002780

Kim, Y., Hertzler, S. R., Byrne, H. K., & Mattern, C. O. (2008). Raisins are a low to moderate glycemic index food with a correspondingly low insulin index. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.), 28(5), 304–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2008.02.015

Attaluri, A., Donahoe, R., Valestin, J., Brown, K., & Rao, S. S. (2011). Randomised clinical trial: dried plums (prunes) vs. psyllium for constipation. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 33(7), 822–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04594.x

Vinson, J. A., Zubik, L., Bose, P., Samman, N., & Proch, J. (2005). Dried fruits: excellent in vitro and in vivo antioxidants. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2005.10719442

Slatnar, A., Klancar, U., Stampar, F., & Veberic, R. (2011). Effect of drying of figs (Ficus carica L.) on the contents of sugars, organic acids, and phenolic compounds. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 59(21), 11696–11702. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf202707y

Razali, N., Mohd Nahwari, S. H., Sulaiman, S., & Hassan, J. (2017). Date fruit consumption at term: Effect on length of gestation, labour and delivery. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 37(5), 595–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2017.1283304

Al-Farsi, M. A., & Lee, C. Y. (2008). Nutritional and functional properties of dates: a review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 48(10), 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390701724264

Al-Shahib, W., & Marshall, R. J. (2003). The fruit of the date palm: its possible use as the best food for the future?. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 54(4), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637480120091982

Hernández-Alonso, P., Camacho-Barcia, L., Bulló, M., & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2017). Nuts and Dried Fruits: An Update of Their Beneficial Effects on Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients, 9(7), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070673

Arjmandi, B. H., Johnson, S. A., Pourafshar, S., Navaei, N., George, K. S., Hooshmand, S., Chai, S. C., & Akhavan, N. S. (2017). Bone-Protective Effects of Dried Plum in Postmenopausal Women: Efficacy and Possible Mechanisms. Nutrients, 9(5), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050496

Rendina, E., Hembree, K. D., Davis, M. R., Marlow, D., Clarke, S. L., Halloran, B. P., Lucas, E. A., & Smith, B. J. (2013). Dried plum's unique capacity to reverse bone loss and alter bone metabolism in postmenopausal osteoporosis model. PloS one, 8(3), e60569. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060569

Evans, S. F., Meister, M., Mahmood, M., Eldoumi, H., Peterson, S., Perkins-Veazie, P., Clarke, S. L., Payton, M., Smith, B. J., & Lucas, E. A. (2014). Mango supplementation improves blood glucose in obese individuals. Nutrition and metabolic insights, 7, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.4137/NMI.S17028

Taleb, H., Maddocks, S. E., Morris, R. K., & Kanekanian, A. D. (2016). Chemical characterisation and the anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and antibacterial properties of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 194, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.032

Wallace T. C. (2017). Dried Plums, Prunes and Bone Health: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients, 9(4), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040401

Kundu, J. K., & Chun, K. S. (2014). The promise of dried fruits in cancer chemoprevention. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP, 15(8), 3343–3352. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.8.3343

Anderson, J. W., Weiter, K. M., Christian, A. L., Ritchey, M. B., & Bays, H. E. (2014). Raisins compared with other snack effects on glycemia and blood pressure: a randomized, controlled trial. Postgraduate medicine, 126(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2014.01.2723

Anderson, J. W., & Waters, A. R. (2013). Raisin consumption by humans: effects on glycemia and insulinemia and cardiovascular risk factors. Journal of food science, 78 Suppl 1, A11–A17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12071

Bagherzadeh Karimi, A., Elmi, A., Mirghafourvand, M., & Baghervand Navid, R. (2020). Effects of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) on labor and delivery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 20(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02915-x

Al-Kuran, O., Al-Mehaisen, L., Bawadi, H., Beitawi, S., & Amarin, Z. (2011). The effect of late pregnancy consumption of date fruit on labour and delivery. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 31(1), 29–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2010.522267

Esfahani, A., Lam, J., & Kendall, C. W. (2014). Acute effects of raisin consumption on glucose and insulin reponses in healthy individuals. Journal of nutritional science, 3, e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2013.33

Bennett, L. E., Singh, D. P., & Clingeleffer, P. R. (2011). Micronutrient mineral and folate content of Australian and imported dried fruit products. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 51(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390903044552

Carughi, A., Feeney, M. J., Kris-Etherton, P., Fulgoni, V., 3rd, Kendall, C. W., Bulló, M., & Webb, D. (2016). Pairing nuts and dried fruit for cardiometabolic health. Nutrition journal, 15, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0142-4

Mossine, V. V., Mawhinney, T. P., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2020). Dried Fruit Intake and Cancer: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 11(2), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz085